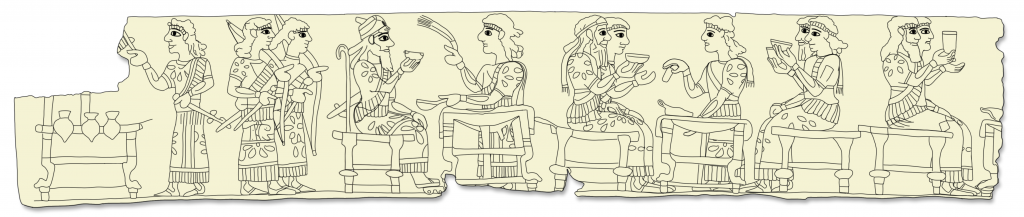

| Object type: Ivory plaque |

| Museum: 59.107.22, Rogers Fund, 1959, The Metropolitan Museum of New York | |

| Findspot: Excavated/Findspot: Room SE 9, Military Palace, Kalhu (Nimrud, north of Iraq) | |

| Culture, period: Neo-Assyrian | |

| Production date: 9th century BCE | |

| Material: Ivory | |

| Dimension: Height: 3.1 cm – Width: 16.5cm – Depth: 0.4 cm |

| Nonverbal Communication: Drinking, Eating, Erect posture, Eye contact, Raising of the hand |

Description:

This ivory plaque is incised with a depiction of a royal banquet. The king sits in the middle and is distinguished by his high-back throne and the crown around his head. The banqueters, privileged guests, are arranged hierarchically: tables closer to the king are occupied by the most important and trusted individuals. It is likely that each table represented a specific rank of officials. The way tables are set suggests that this is a sociopetal setting, the aim being to facilitate and promote interaction between banqueters.

All the banqueters, including the king, are equated by posture and gesture. The erect posture, which seems conventional for Assyrians according to the Assyrian visual evidence, was considered to carry positive connotations of appearing agreeable, while holding the head high indicated correctness and dignity. Moreover, this posture was an element which expressed reciprocity because it implied direct eye-contact between banqueters.

One gesture which both banqueters and the king himself perform is the raising of their beakers. Such a gesture diminishes the differences between banqueters, since raising beakers may have meant that men are toasting one other and this very scene of conviviality made the partakers similar in status. Each banqueter balances a bowl or beaker containing wine in one hand, making use of all his fingertips. This elegant mannerism may have been the natural way to display the access to wine and its social consequences.

Everyone, from the king and queen to the peasant and his wife, ate with their hands. Nonetheless, the high-level of hygiene is shown by the fact that each banqueter or group is attended by a servant who provides food and drink and, according to textual evidence, also receives dirty napkins and gave out clean ones.

Bibliographic references:

Herrmann G. 1992: Ivories from Nimrud (1949-1963): The Small Collections from Fort Shalmaneser, Fasc. V, London, 79, no. 185, pl. 39.

Collins P. 2018: “Life at Court.” In: G. Brereton (ed.), I am Ashurbanipal, King of the World, King of Assyria, London, 44-45, fig. 45.

Portuese L. 2020: “The Decoration of the Southwest Wall of Façade n at Dur-Sharrukin: Adjustments and Significance”. Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 2020/2, 161, fig. 2.

Portuese L. 2023: The Assyrian Royal Banquet: A Sociological and Anthropological Approach. In: S. de Martino / E. Devecchi / M. Viano (eds.), Eating and Drinking in the Ancient Near East, Proceedings of the 67th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale held in Turin, July 12-16, 2021. Dubsar 33. Münster: Zaphon, 353–364.

©Image credits: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Drawing by Steve K. Simons.